The “new normal” has taken a “new” twist. For decades, the privilege of working from home seems like it has been largely reserved for elite, white-collar workers. In a matter of weeks, the COVID-19 crisis forced millions more workers into remote work—and a recent survey finds that many prefer keeping that arrangement.

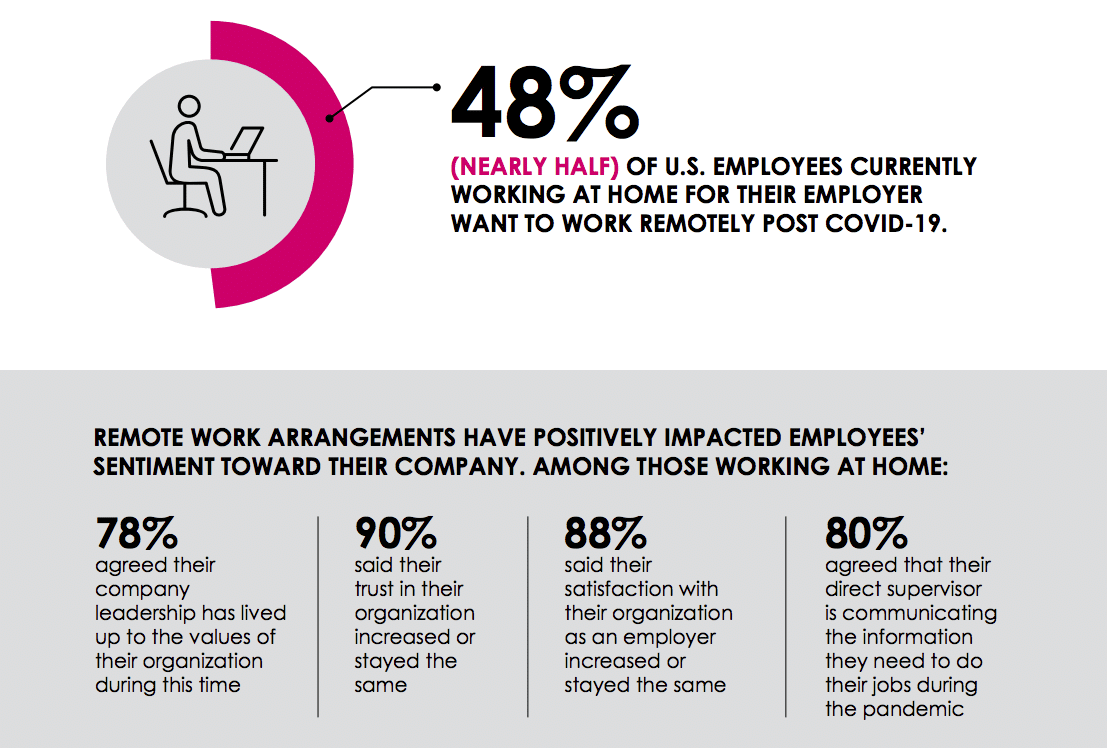

About half (48 percent) of employees working from home now say they’d like to continue working from home, according to a new employee survey from The Grossman Group, a Chicago-based leadership and communications consultancy. The research reveals that many employers were surprised by how quickly employees adjusted in the early days of COVID-19, which prompted these survey questions about employee preferences and whether remote working options should expand.

Clearly, employee work preferences still differ and working from home is not for everyone—either because employees simply cannot do their jobs remotely or would prefer not to. Still, the survey findings are a clear signal to employers that employee preferences are rapidly evolving and that it’s time to rethink traditional ways of working, according to David Grossman, founder and CEO of The Grossman Group.

“A great deal has changed in employees’ work lives in a short time, and if we want them to be engaged and productive, we’re going to have to be willing to meet them where they are as much as possible,” said Grossman, in a news release. “Many employees have gotten a taste of working from home for the first time, and they like it. Others can’t wait to get back to the office. We encourage employers to help their people work wherever they can be at their best, to the extent that’s possible. That’s a ‘win-win’ for companies and their people.”

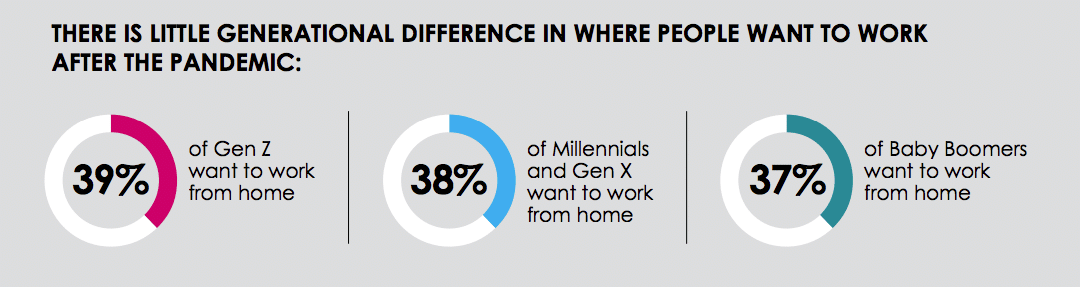

Curious about the employee perspective, the agency examined the preferences of different employee groups for when the pandemic subsides and offices re-open. Overall, the employees surveyed who are working from home had high marks for their employers’ response to the pandemic. This may have helped build their confidence in a remote working situation for the long-term.

Some employers may find the growing interest in remote working difficult to accept, as it represents a large shift from the norm of only a couple months ago. Prior to COVID-19, only 7 percent of U.S. private sector workers had access to a “flexible workplace” benefit, or telework, according to a prominent study of the U.S. Workforce—the 2019 National Compensation Survey (NCS) from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. Many of those teleworkers were managers or other white-collar professionals.

Thinking outside the box to identify new working arrangements that could be mutually beneficial to both the employer and employee is critical today, Grossman says. During the pandemic, even employers who traditionally expected employees to be in the office most of the time learned just how capable and resourceful employees can be, no matter where they are, he says.

Further, many studies have shown that employees who work from home are at least as productive or more productive than those in the office. A frequently cited 2015 study by Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom reported many benefits from working from home, including higher productivity and a lower attrition rate. However, that prominent study produced cautionary findings, as well. Bloom found that many employees in the company he studied later changed their mind about wanting to work from home 100 percent of the time, as they felt too isolated. This led Bloom to recommend working from home a few days a week rather than constantly.

This type of research supports Grossman’s own experience. “Many employees will be productive no matter where they are,” Grossman said. “A one-size-fits-all approach is not the wave of the future. More flexibility adds value to the employee experience, builds engagement, and brings results.”

Download the key report findings here.

The Grossman Group conducted the online survey of 841 current U.S. employees across a variety of sectors from April 27 to May 1, 2020. Raw data were weighted by five variables (age, sex, geographic region, race and education) to ensure a reliable and accurate representation of the U.S. population, based on U.S. Census data. The margin of error for the data is +/- 3.4 percentage points.