Among the many shakeups caused by the pandemic, the ever-shifting “new normal” workplace is one of the most significant—and its effect on leadership is now being realized. A new study from research consortium Future Forum reveals that executives’ work-experience scores have worsened significantly over the past year as leaders struggle to adapt to new employee expectations and adjust their management strategies.

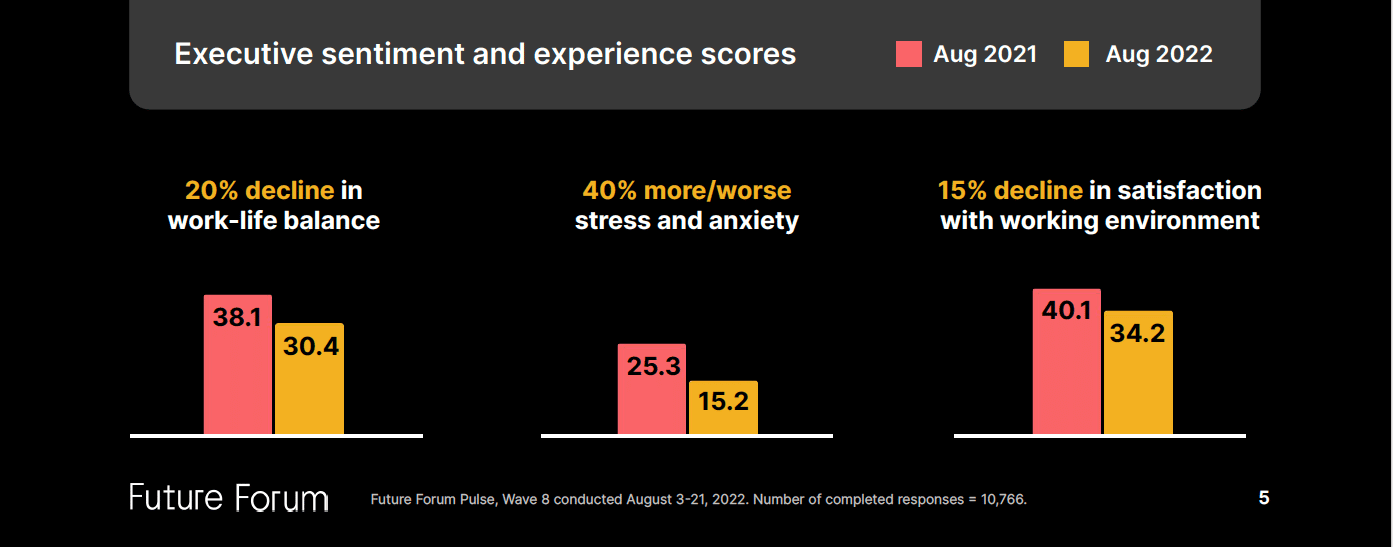

The new Global Pulse report from Future Forum, launched by Slack with founding partners Boston Consulting Group, MillerKnoll and MLT to help companies redesign work in the new digital-first workplace, shows that execs’ overall satisfaction with work is down 15 percent over the last year.

But as executives have faced challenges leading teams in a changing world, employees with flexibility at work have reported positive changes within their companies

Remote and hybrid workers were 52 percent more likely to say their company culture has improved over the last two years compared with fully in-person workers—and they cite flexible work policies as the primary reason their culture is changing for the better. These findings suggest that a hard return to pre-pandemic ways of working will be counterproductive when it comes to strengthening culture and boosting productivity. Instead, leaders need to focus on more meaningful management changes to address serious underlying issues in the workplace, like burnout and attrition.

“We’re still in the middle of the biggest workplace paradigm shift we’re apt to see in our lifetimes, and leaders are feeling that pressure,” said Sheela Subramanian, vice president and co-founder of Future Forum, in a news release. “The macroeconomic conditions, the continuing Great Resignation, and the push-pull between executives and employees on issues of workplace flexibility are making it harder to lead with confidence—you can no longer rely on the old leadership playbooks.”

Leaders are facing new challenges caused by shifting workplace expectations and norms, and falling back on old habits

Decades’ worth of change happened overnight for most companies at the onset of the pandemic, forcing executives—most who rose to the top in pre-pandemic work cultures—to navigate an uncharted and turbulent work environment. In the face of these challenges, executives themselves are struggling: they’re reporting record low experience scores, including 40 percent more work-related stress and anxiety and 20 percent worse work-life balance, year-over-year according to the study. Leaders in the middle of the management structure are also straining under these demands; of all workers surveyed, middle managers reported the lowest scores for work-life balance, along with the highest levels of stress and anxiety.

Leaders who respond to new stressors by pushing for old ways of working—such as issuing top-down mandates calling workforces back to the office full-time—are likely to experience resistance from their employees. Executives are far more likely than non-executives to say they’d like to spend the majority of their time in the office: 38 percent of executives say they would prefer to work from the office 3-4 days a week, compared with just 24 percent of non-executives. And non-executives are more than 3x as likely as their bosses to want to work fully remotely.

In the meantime, workplace planning continues to largely happen at the executive level, with 60 percent of executives saying they’re designing their companies’ policies with little to no direct input from employees. This should raise alarm, as the data shows that executives’ own work experience is not representative of the typical employee experience.

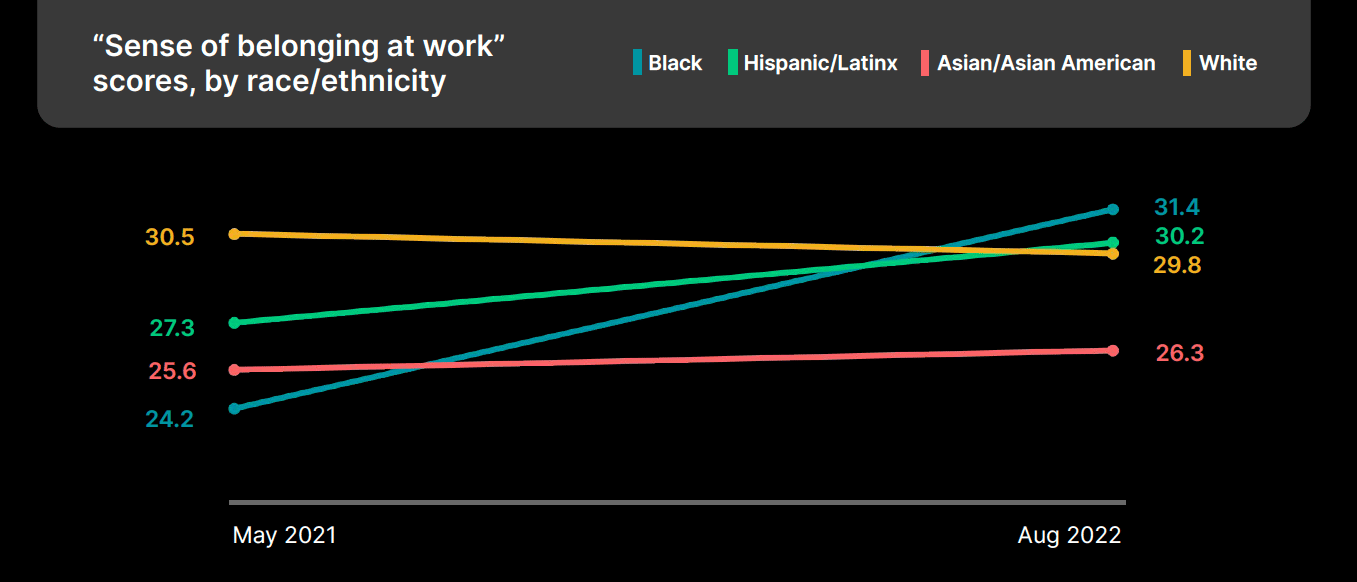

While experience scores dropped for executives, scores are rising for other groups year-over-year. Individual contributors have seen notable gains including 11 percent greater work-life balance, 25 percent less stress and anxiety, and 6 percent higher productivity over the last year. In the U.S., Black employees also made significant gains, and are now reporting the highest scores of any racial/ethnic group across many measures, including workplace flexibility, ability to focus, sense of belonging, and overall workplace satisfaction.

“Returning” is the wrong direction to build a productive work environment

Future Forum data shows that the push to return to pre-pandemic work policies—whether because of executive preference, or in an effort to improve company culture and productivity—is likely counterproductive. In fact, providing employees with flexibility has been shown to have a positive impact on these key factors:

- Productivity: Executives cite declining productivity as their second most serious concern when it comes to flexible work. But the data disproves this opinion: in reality, flexible work is associated with higher productivity and focus, not less. Workers with location flexibility report 4 percent higher productivity scores than fully in-office workers, a difference that across a workforce can add up to material improvements to the bottom line. The benefits of schedule flexibility are even greater. Future Forum data shows that workers who have full schedule flexibility show 29 percent higher productivity than workers with no ability to shift their schedule.

- Culture and connection: 25 percent of executives cite “team culture is negatively impacted” as their number one concern about offering employees more flexibility. But new data supports the view that flexible work enhances company culture, not harms it. Remote and hybrid workers cite flexible work policies as the top reason their company culture has improved over the last two years. Remote and hybrid workers are also more likely to feel connected to their manager and their company’s values than in-office workers, and just as likely to say they feel connected to their immediate teams.

“If you’re thinking in terms of ‘returning’—returning to the old way, returning to the way the office used to be, returning to what worked for you—then it’s time to rethink that direction,” said Ryan Anderson, vice president of global research and insights at MillerKnoll, in the release. “We need to move forward to a new path, and that requires engaging your employees to establish new ways of working together.”

Leaders should refocus on solving issues like burnout to foster a stronger work environment

The latest data show that leaders who wish to build healthy and productive work cultures would benefit from refocusing their attention on a growing crisis among desk workers: burnout. The percentage of desk workers globally who say they are burned out rose to 40 percent this quarter (43 percent in the U.S.). And the consequences of burnout are severe: employees who are burned out report 22x worse stress and anxiety at work compared with employees who are not. Burnout is closely associated with degraded employee performance, including 32 percent worse productivity and 60 percent worse ability to focus.

There’s also a troubling gender gap between women and men on the issue of burnout, with women reporting 32% more burnout than men. In addition, younger groups are more likely to experience burnout, with 49 percent of 18-to-29 year olds saying they feel burned out, as compared with 38 percent of workers age 30+. By job level, middle managers are at the greatest risk of burnout (a whopping 43 percent), while 32 percent of executives say they’re experiencing burnout.

Burnout is a major contributor to attrition and the Great Resignation. People who are burned out feel far less connected to their companies and report being 3x more “likely” or “very likely” to look for a new job in the coming year. With burnout on the rise this quarter, the number of desk workers who say they are likely to look for a new job in the next year rose to 57 percent. Women, working mothers, and people of color are most likely to say they would like to change jobs.

Counter burnout by giving employees more choice and flexibility

Future Forum’s research shows that flexibility is highly desired, ranking second only to compensation when it comes to what determines workplace satisfaction. But flexibility isn’t just about location—while 80 percent of workers say they want flexibility in where they work, 94 percent say they want flexibility in when they work.

Providing employees with schedule flexibility is an effective, yet so far rarely supported, way to reduce burnout and increase employee engagement and loyalty, while also improving business outcomes. Employees with schedule flexibility show the highest scores across the board on our index, including 53 percent greater ability to focus and 3x better work-life balance. On the other side of the spectrum, employees with no schedule flexibility are more than twice as likely to look for a new job in the coming year, compared with employees with moderate schedule flexibility.

Leaders can provide schedule flexibility today by adopting practices like core work hours and team-level agreements. Using digital tools can also help teams collaborate more asynchronously so that individuals have greater flexibility to structure their days. The payoff for this investment in new ways of working is better business outcomes. Employees who work for companies they describe as innovators or early adopters of technology report 1.5x greater productivity, 2.2x higher sense of belonging, and 27 percent less burnout than those who work for “digital laggards.”

Download the full report here.

This Future Forum Pulse surveyed 10,766 workers in the U.S., Australia, France, Germany, Japan and the U.K. between August 3 – August 21, 2022. The survey was administered by Qualtrics and did not target Slack employees or customers. Respondents were all desk workers, defined as employed full-time (30 or more hours per week) and either having one of the roles listed below or saying they “work with data, analyze information or think creatively”: executive management (e.g. president/partner, CEO, CFO, C-Suite), senior management (e.g. executive VP, senior VP), middle management (e.g. department/group manager, VP), junior management (e.g. manager, team leader), senior staff (i.e. non-management), skilled office worker (e.g. analyst, graphic designer). For brevity, we refer to the survey population as “desk-based” or “desk workers.”