In the 1997 movie “Liar, Liar,” Jim Carrey plays Fletcher Reede, a highly successful lawyer with a propensity for compulsive lying. He suddenly finds himself unable to tell anything but the truth, the whole truth, so help him … well, you know the rest.

In the 2009 movie, “The Invention of Lying,” Hollywood revisited the premise. In that film, honesty is the only policy (until someone—Ricky Gervais’ screenwriter character Mark Bellison—figures out that maybe it isn’t).

Of course, in real life, such a dedication to candor is not nearly so absolute.

Not all deceptive statements are egregious. Who hasn’t told a fib or white lie to spare the feelings of another? But some deception has the power to do more than affect the feelings of just one person.

Disinformation, when sown publicly by politicians, businesses, industry experts, and other leaders, can have a far more lasting impact on many more lives.

Let’s begin with what we usuallyadvise. As a spokesperson or subject matter expert, you may find yourself in a media interview looking for a way to counter false allegations or misstatements. Typically, we advise clients not to repeat what you have been accused of in your response. So, rather than saying “I am not a crook”—which looks defensive and pairs you with the negative accusation—it’s best to say, “I have always complied with the law.” You can read more about avoiding the “language of denial” here.

But we’re in unprecedented times of disinformation being spread by bad actors with ill intent, so it may be time to revisit our previous advice.

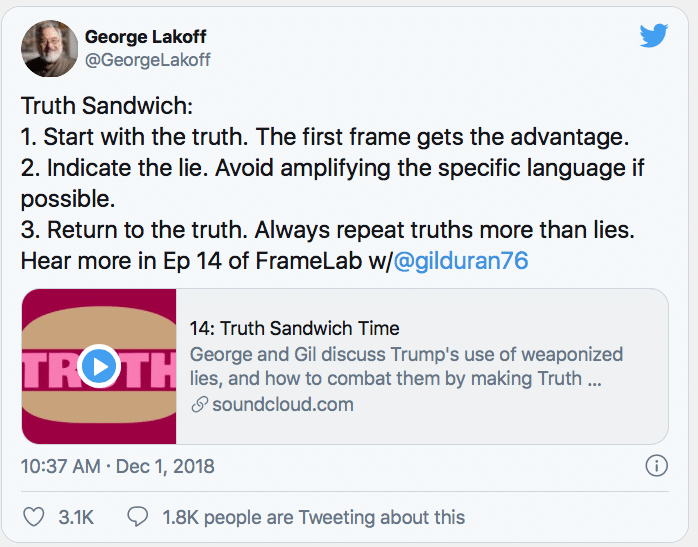

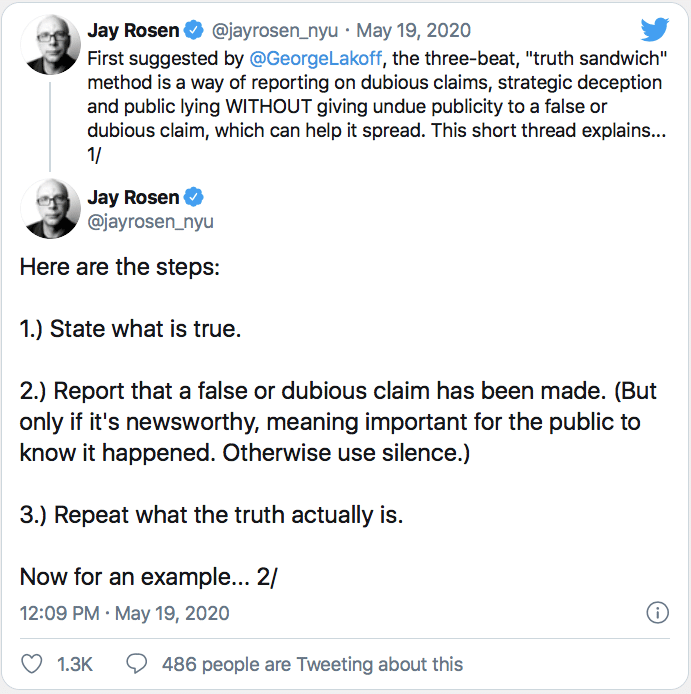

Earlier this year, on Twitter, author and professor Jay Rosen, who teaches journalism at New York University, offered up the concept of a “truth sandwich” for reporting (or commenting) on false or dubious claims. He referenced the method’s originator—George Lakoff, an emeritus professor of cognitive science and linguistics at UC Berkeley.

First, here’s Lakoff’s concept:

Rosen then shared his take on the three steps:

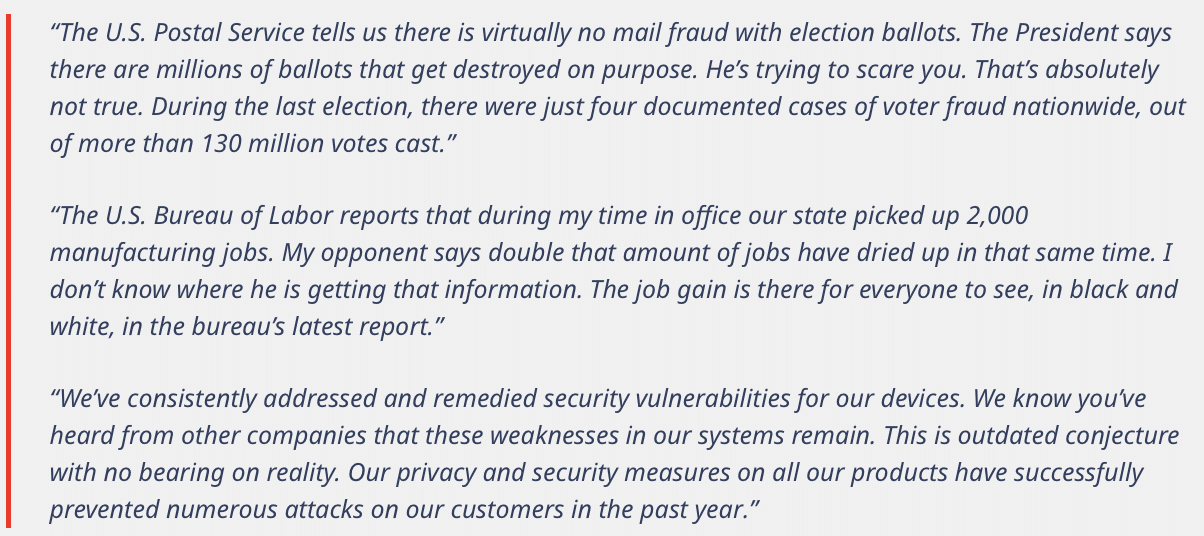

The idea is that you can contain the spread of faulty logic or incorrect assertions by “sandwiching” it between true statements. Debates over whether this should be called a “lie sandwich” aside, we provide some examples of how one might counter questionable information below. (These are hypothetical examples inspired by real-life events.)

“We’ve consistently addressed and remedied security vulnerabilities for our devices. We know you’ve heard from other companies that these weaknesses in our systems remain. This is outdated conjecture with no bearing on reality. Our privacy and security measures on all our products have successfully prevented numerous attacks on our customers in the past year.”

When should you use this?

As is indicated in Rosen’s how-to, using a “truth sandwich” to counter a claim in which the veracity is questionable comes down to a judgment call. Would the audience that matters to you consider the claim newsworthy? Can you counter it with certifiable and legitimate truth? What will you gain by calling out the offender?

More broadly, is this honestly worth a comment?

There are always trade-offs in the decisions you make to counter disinformation. By pushing back with a “truth sandwich” you repeat the lie or inaccurate comment the person has said. Typically, that’s not what we advise people to do, as the very statement you are trying to debunk may be the only one of your quotes the reporter uses—which is completely counterproductive to your intent.

As with any tool, there are times it’s more effective than others, such as during a political debate or live media interview. If you are being interviewed for a print or online article with an adversarial reporter or news outlet, you might want to take the “truth sandwich” off the menu.

This article originally appeared on the Throughline blog; reprinted with permission.